Temperament, Character and the Work of Formation

Our temperament shapes the way we look at reality

The human person is a mystery. Little by little, anthropology and psychology are revealing aspects that were previously undeveloped. Temperament and character knowledge is important in formation work.

Complete with Online Temperament Test

Temperament and character have been spoken of since classical antiquity as two key elements of the human personality by such thinkers as Hippocrates, Aeschylus, Pindar, Plato and Aristotle. The science of character – virtue – has been much studied in Christian philosophy; however, the science of temperament is quite a recent development, having been championed by Catholic and secular thinkers in the last century.

The science of temperament, like that of character, provides important coordinates for self-knowledge and personal growth without ever exhausting the richness, value and mystery of the image of God in each person. In the task of spiritual direction, the important thing is to see these traits, both of temperament and character, as part of the talents that each person possesses and to guide the person on the best way to make them bear fruit.

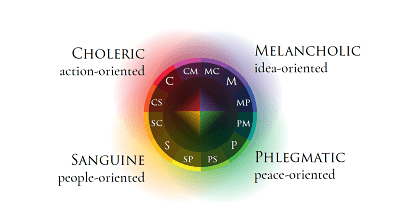

In this presentation, the types of temperaments are succinctly presented based on the classical distinctions of choleric, melancholic, sanguine and phlegmatic. Furthermore, some ideas are presented in a schematic way to help in the formation of virtues according to the temperament type.

Temperament and Character to grow and improve your formation

Temperament is a natural and innate predisposition to react in a certain way. It is a gift of nature and, ultimately, a gift of God. Our choleric, melancholic, sanguine or phlegmatic temperament cannot be changed. To want to change it could imply a certain disorder. We will die with the innate qualities and defects of our temperament; however, we can integrate and subdue them so as to take advantage of them in our quest for virtue.

The four temperaments are defined as follows:

- The choleric is distinguished by his immediate, energetic and lasting reactivity.

- The melancholic is distinguished by his delayed, deep and lasting reactivity.

- The sanguine is distinguished by his immediate, spontaneous and ephemeral reactivity.

- The phlegmatic is distinguished by his delayed, measured and ephemeral reactivity.

- The choleric is energetic: he is oriented to action.

- The melancholic is deep: his life revolves around ideas.

- The sanguine is spontaneous: he lives from and for his relationship with people.

- The phlegmatic is restrained: above all else, he seeks peace.

Our temperament inclines us in one direction or another: the choleric is inclined to do many things, but finds it difficult to care about people; the melancholic is inclined to contemplate beautiful ideas, but finds it difficult to put them into practice; the sanguine is inclined to share his feelings with others, but finds it difficult to put the finishing touches on his projects; the phlegmatic tends to analyze processes, but finds it difficult to dream great things.

Virtues, temperament, character and formation

Virtue compensates for the defects of our temperament: the choleric who practices humility is concerned about people; the melancholic who practices audacity/daring accompanies it with action; the sanguine who practices endurance completes his projects; the phlegmatic who becomes magnanimous dreams great things. Each temperament climbs the summit of excellence by a path and a slope that is proper to it , indicating its itinerary.

It is important to distinguish between physiological and spiritual factors when discerning ways forward. For instance, physiological energy is not strength, but it favors it; equally, physiological apathy is not laziness, but it favors it. Thus, there are two extremes to be avoided: one consists in denying the reality of character, the other in denying the reality of temperament. The first error is “determinism” and the second is “voluntarism”.

Determinists deny the spirit, character, virtue and the action of God’s grace, interpreting human actions exclusively from the point of view of biology and genetics. By justifying their base actions as the peculiarity of their temperament, determinists are in fact denying their freedom, their responsibility, their dignity, and that of others.

The voluntarist character

Voluntarists, on the other hand, deny temperament. They interpret human actions exclusively from the point of view of the will and of freedom. They conceive physiological tendencies as spiritual defects. In the tireless action of the choleric they see nothing but pride; in the creative self-absorption of the melancholic, selfishness; in the joie de vivre of the sanguine they see a lack of self-control, and the phlegmatic is, in their opinion, nothing but lazy and idle.

The voluntarists love spiritual uniformity and do not easily tolerate diversity of behavior. They have only one model of excellence in mind: the model forged by their own temperament. They often accuse those who speak of diverse temperaments as categorizing or pigeon-holing people, when, in fact, they themselves are guilty of placing all of humanity into a single category: that of their own temperament. By doing so, they unwittingly place others with different temperaments into a spiritual prison.

It goes without saying that a good spiritual director will have to overcome the obstacle of voluntarism. A person who practices spiritual direction will have to have a minimum knowledge of the temperament of the person with whom he speaks, enabling him to take into consideration the physiological inclinations of the other. Without this, he may easily come to erroneous conclusions: seeing pride in the choleric, selfishness in the melancholic, lack of self-control in the sanguine, and laziness in the phlegmatic. Consequently, he will not be able to help his brother very much. In fact, he could very well do him harm.

The Challenges of Each Temperament to form a good Character

In this section, we will review, in broad stroke, the strengths and weaknesses of the different types of temperaments as they relate to fundamental virtues, thereby identifying ways in which to encourage their development.

The Choleric

The choleric is energetic: he is oriented to ACTION.

⇰ Strengths:

- Energy, enthusiasm, decisiveness.

- Self-confidence: he is aware of his talents.

- A born entrepreneur: he starts numerous projects.

- A manager by nature: able to move things forward quickly.

- He likes power: he thrives on competition.

⇰ Weaknesses:

- He is inclined to pride and anger.

- Does not take time to think before deciding.

- Is inclined to blind activism.

- Tends to confrontation and dictatorship.

- He does not easily recognize his mistakes.

- In managing people, he finds it difficult to respect the feelings of others, to make them grow and take responsibility, and to serve them.

Prudence

The choleric person has no difficulty in making decisions. In the process of deliberation, he must practice self-control, moderating his natural impatience, and humility, learning to ask for advice on a regular basis. However, paying more attention to deliberation should not hinder his natural capacity for decision-making: the goal of prudence is not to deliberate but to decide. Not deliberating is bad, but not deciding is even worse: it is a fundamentally imprudent act.

Fortitude

The choleric person does not have any special difficulties in practicing fortitude, for audacity and resilience come naturally to him.

Self-control

For the choleric, self-control should consist fundamentally in practicing humility and gentleness:

- humility: he must understand that his physiological strength is not the result of personal effort, but a gift.

- gentleness: he must learn to control his tongue and not to interpret the opinions of others, when contrary to his own, as a declaration of war.

Justice

Since the choleric is action-oriented, he easily participates in the development of the common good; however, on one condition: he must know what it is and be determined to promote it.

Interpersonal communion, on the other hand, constitutes a real challenge for the choleric. He has a tendency to be confrontational and dictatorial, to despise those who are less energetic than he is. He needs humility to listen to people and understand them, not to humiliate them, not to hurt their feelings, not to violate their dignity and their freedom in the name of a sacred cause or an objective to be achieved at all costs.

Magnanimity

The choleric person has a tendency to set high goals and to achieve them. However, he also has a tendency towards a certain blind activism. He needs to reinforce the contemplative side of his personality: his action must constitute an extension of his being, the result of the contemplation of his dignity and his greatness. There are many choleric people who act for the pleasure of acting, to reach some objectives or to fill the emptiness of their inner life. For the magnanimous, action is the fruit of self-knowledge; it never degenerates into “activism”.

Humility

The choleric is aware of his talents. This is an important aspect of humility, which is the virtue of those who live in the truth of themselves. But the choleric finds it difficult to live the rest of the aspects of humility, particularly service to others. He pushes rather than pulls, commands rather than inspires, controls rather than teaches. Exerts power rather than giving those he leads the possibility of assuming responsibility and fulfilling it. No friend to delegation because he is convinced that he does things better and faster than others and because he enjoys action. The choleric person needs above all to cultivate fraternal humility. Fraternal humility is his personal challenge.

The Melancholic

The melancholic is deep: he revolves around the IDEA.

⇰ Strengths:

- Inclined to contemplation.

- Seeks perfection in everything.

- Independent.

- Patient and persevering.

⇰ Weaknesses:

- He has a tendency to be absorbed by his thoughts and feelings.

- He fears action, in which the imperfection due to human limitation is irremediably manifested.

- He fears uncertainty; he does not like to take risks.

- He is inclined to pessimism.

- He worries about unimportant things.

- He works poorly in teams, preferring to do things his own way.

- He is easily offended and tends to criticize others.

Prudence

The melancholic is deep but he has a tendency to pessimism: he exaggerates difficulties. In the deliberation process, he needs realism and optimism. In the decision-making process, he needs boldness. He likes the “idea” which is always perfect in his heart and on paper but fears action, in which human imperfections are irremediably manifested. The melancholic must overcome his fear of the unknown. He must get used to taking risks.

Fortitude

The melancholic easily practices perseverance because he is profound and knows how to discover the meaning of suffering. However, he needs audacity. Preferring analysis to action, he is very cautious and intimidated by the unknown. The melancholic needs audacity above all. Boldness is his personal challenge.

Self-control

The melancholic is easily stimulated by noble passions. However, he must learn to master certain inner tendencies, such as pessimism (focusing only on the negative side of reality), sadness (he is subject to mood changes), anxiety (he worries about unimportant things), critical spirit (he readily criticizes others and their projects), susceptibility (he finds it difficult to forget the offenses he has suffered). Pessimism and anxiety can be overcome through realism by telling himself, “In reality, things are not so bad! 90% of the problems that make me feel bad only exist in my imagination!”. His critical spirit and susceptibility can only be overcome through love. The certain sadness of the melancholic temperament will probably accompany him throughout his life. However, it can be overcome by refusing to give in to despair and by maintaining a sense of humor.

Justice

The melancholic wants to contribute to the common good, he is an idealist. However, he will not be able to realize his dream unless he develops daring. Interpersonal relationships are a challenge for the melancholic because his self-absorption in thoughts, feelings and emotions makes it easy to forget or overlook others. He also has a tendency to bear grudges over time and to criticize others, even if only internally. He must learn to work in a team in order to overcome his love of doing things his own way.

Magnanimity

The melancholic is easily magnanimous from the point of view of contemplation: he knows how to dream and has a facility for setting noble and lofty goals. However, from the point of view of action, he has a tendency to be faint-hearted. He must learn to be bold in order to overcome his pessimism and his fear of the future.

Humility

The melancholic usually possesses a good level of self-knowledge. He is aware of his talents and rejoices in the thought that it is not his own, but a gift from God. However, he finds it difficult to serve because of his tendency to be self-absorbed. Striving to live the virtues of interpersonal relationship – empathy, friendship, joy – will help him to overcome his self-absorption. Only then will he make the most of his talents.

The Sanguine

The sanguine is spontaneous: he lives from his relationship with PEOPLE.

⇰ Strengths:

- He loves people and wants to make them happy.

- He is friendly, compassionate, communicative.

- He is enterprising and loves adventure.

- His external senses are always awake: he pays attention to every detail.

⇰ Weaknesses:

- Poorly controls his external senses: hearing, sight, smell, taste, touch.

- Amusement may become a main or almost exclusive aspect of his motivation.

- He tends to superficiality and instability.

- He is attracted to everything new.

- He wants to please and to be loved by everyone.

Prudence

The sanguine likes to make decisions because he loves adventure. However, in the process of deliberation, he must strive to overcome superficiality which permanently threatens him. “Believe me, this is going to work!”, he affirms without seriously thinking about what he is saying. The sanguine must take reality as it is.

Fortitude

The sanguine is often audacious: he gets bored if there are no novelties, intrigues, adventures or entertainment. At the same time, he can also be fickle in his feelings, in his thoughts, in his work. His enthusiasm leads him to go after something new every time. The sanguine must train in endurance, stability, fidelity and patience. He must strive to put the last stroke on each of his projects. The sanguine needs endurance above all. Endurance is his personal challenge.

Self-control

If cholerics and melancholics must mortify their internal senses, sanguines, on the other hand, must learn to control their external senses. They love to live by sensation. The sanguine must strive particularly to mortify his sight: like a magpie, he is attracted to everything that shines. He enjoys the luxurious life, elegant clothes and sports cars. If the choleric can be said to live in the future and the melancholic in the past, the sanguine is at ease in the present.

Justice

The sanguine is naturally sociable and open. He easily lives the virtues related to interpersonal relationships. However, in order to build the common good, he must overcome his instability. He must practice the virtues of perseverance and fidelity.

Magnanimity

To be magnanimous, the sanguine must overcome his superficiality and instability.

Humility

The sanguine is ready to serve. However, in order to serve truly and effectively, he must strive to practice endurance, stability and fidelity.

The Phlegmatic

The phlegmatic is restrained: above all, he seeks PEACE.

⇰ Strengths:

- His approach to reality is dispassionate and scientific.

- He is a good listener and empathetic.

- He has a deep sense of duty and a good spirit of collaboration.

- He has an iron will, almost always hidden; he is constant and persevering.

- It is difficult to make him lose his temper.

⇰ Weaknesses:

- He likes the status quo, and is averse to anything out of the ordinary.

- He avoids conflict at all costs.

- He is afraid of being wrong.

- He is easily overpowered.

Prudence

The phlegmatic is possessed of good judgment, which allows him to think effectively. However, he finds it difficult to make up his mind. The thought that he might make a mistake weighs on him. He must practice boldness, because the essence of the virtue of prudence is not deliberation but decision. Prudence is not cautious inaction but intelligent action.

Fortitude

Resistance is no challenge for the phlegmatic: he has an iron will, though not externalized. He is patient in difficult situations. He is constant and persevering. However, fortitude is not simply resistance. It is also audacity. Boldness is difficult for him because he is comfortable with routine and the status quo and trembles at the thought of making a mistake.

Self-control

The phlegmatic easily controls his passions, because their intensity is limited. He must, however, stimulate his noble passions and overcome his fear of conflicting situations. While loving peace (he has no difficulty in doing so), he must also be willing to sacrifice it for a higher value.

Justice

It is easy for the phlegmatic to be just because of his deep sense of duty. However, in order to build the common good, he must learn to overcome his apathy.

Magnanimity

Magnanimity is a real challenge for the phlegmatic: he must learn to dream, to develop a sense of his own worth, to discover and affirm his talents. He must develop his capacity for action as well as for contemplation. The phlegmatic is, above all, in need of magnanimity: this is his challenge.

Humility

The phlegmatic likes to be of service. However, he must learn to discover his talents and make them bear fruit in order to serve others effectively.

Temperament Mixtures and Temperament Tests

Temperaments are not usually “pure”. It is usual for a person to have a mixture of two in which one is dominant and the other secondary. In this way, the secondary temperament can help compensate for certain defects of the primary temperament. For example, a person with a choleric primary temperament who has a melancholic secondary temperament will be more likely to practice deliberation (prudence) than a person who is 100% choleric. Similarly, a person who is predominantly melancholic, but has a secondary trait of choleric will be more likely to make decisions (prudence) than if he were 100% melancholic.

The secondary temperament

The secondary temperament can help to meet the personal virtue challenge. For example, sanguine/phlegmatics or sanguine/cholerics will find it easier to practice endurance than if they are 100% sanguine. If you are phlegmatic/sanguine or phlegmatic/melancholic, it will be easier to practice magnanimity than if you are 100% phlegmatic. A melancholic/choleric will find it easier to practice boldness than a person who is simply melancholic. The choleric/sanguine will find it easier to practice humility than a 100% choleric.

Experts often indicate that the choleric/phlegmatic and melancholic/sanguine temperaments are impossible combinations. In addition, it sometimes appears that a person possesses a mixture of the four basic temperaments; this, however, is a mistaken impression, although it probably reflects something positive: it means that the person has developed his or her character, building virtues on his or her temperament.

There are many temperament tests both in books and on websites. We propose the following one: Alex Havard Test, know how you are.

When answering temperament test questions, do not be afraid of the result. Remember that it is not about character but about temperament. It is about our primary reaction, the physiological reaction, to an external stimulus. The better we identify this type of reaction, the more accurate the results of the tests will be.

Possible Questions for Dialogue about temperaments

- How could we help people in the work of formation to know their temperament and to see their potentialities with gratitude? Wouldn’t knowing and talking about their temperament be a way of helping people to be simpler, to let themselves be known as they are?

- How could it be explained that this does not imply a deterministic vision of the person and that the important thing is to forge one’s character? How can we help confront some negative tendency of the temperament, in an encouraging way, setting attainable goals?

- The word “character” has been used a lot to talk about temperament in the past. For example, many say “he has a strong character” when talking about physiological traits (but not moral virtues). Would it be worthwhile to better differentiate the two when speaking or writing?

- Could we try to discover the temperaments of some biblical characters, such as Moses, David or New Testament saints like St. Paul, St. Peter or St. John.? Perhaps we could also explore saints closer to us in time, such as St. Josemaría or Blessed Álvaro? In what ways did their temperament form their character?

Bibliography about temperament and character in formation

Havard, A. From Temperament to Character, Scepter. Translations available in ten languages; in Spanish: Del temperamento al carácter (2018).

Bennet, A. and L. (2005). The Temperament God Gave You. Sophia Institute Press, Manchester, NH.

Alexandre Havard